By Shah Zaman Farahi

Background

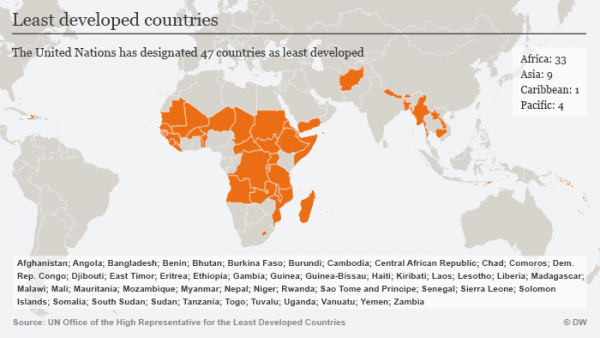

The fourth United Nations conference held on the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in May 2011, convened in Turkey, adopted the Istanbul Programme of Action (IPoA) for LDCs for the decade 2011 – 2020. IPoA presents the international community’s commitment and engagement to graduate at least half of the 47 countries from the LDC category by 2020. In 1971, the United Nations recognized the Least Developed Country (LDC) category to classify countries that are at high risk and are stagnantly underdeveloped. The population of the LDCs exceeds 880 million people and accounts for less than 2 percent of GDP, reported on the IPoA website. The criteria for graduation are income, human assets index and economic vulnerability. So far, the expected countries to graduate are Vanuatu by 2020, Angola by 2021, Bhutan by 2023, São Tomé and Prícipe by 2024 and the Solomon Islands by 2024.

The IPoA considers country contexts and has devised a process to achieve its eight objectives for the LDCs. The LDCs have different characteristics attributed to their natural geographic locations, weather conditions, institutional setups, population and terrain, among others. The mid-term evaluation of the program notes weak growth and a lack of progress towards graduations. The lessons learned report recommends mainstreaming the IPoA into LDCs’ national plans and draws on some achievements of some of the LDCs.

Evaluating the to-date progress, the country context, policy integration, streamlining IPoA in planning and integrating it in cyclical development strategies, the likelihood of Afghanistan graduating from LDCs category by 2020 or another decade, remains low. Deteriorating security due to conflict threatens to erode the gains of the last decade in Afghanistan. It is one of the significant impediments to the achievement of the IPoA or equitable economic growth. Philip Barrett estimates the cumulative revenue loss due to conflict[1] from 2005 – 2016 amounts to a staggering 140 percent of the government revenues.[2] The revenue loss severely restricts the government’s ability to use its national budget as a tool to deliver on the defined criteria defined under IPoA.

Two of the main parameters that could potentially derail any LDC’s efforts to graduate are the shifting political landscape and the insecurity affecting development gains, among other factors. This brief text examines Afghanistan’s graduation prospects based on the IPoA objectives, process and criteria that can be found on UN-OHRLS.

Afghanistan’s progress

Afghanistan has made significant achievements in health and education primarily. From 2011 to 2017, there has been (almost) a 6-percent increase in the country’s human development index rising to 0.498. However, the economic transformation decade of 2011–2020 had some significant setbacks. The economic growth rate has averaged to two percent (2%) since 2014; the growth rate feels shy from the annual seven (7%) percent target set under IPoA. As a result, GDP per capita declined to USD 520 in 2018 from USD 641 in 2012.[3] Poverty increased to an estimated 54.5 percent in 2016/2017 amid the deteriorating conditions in the country. The employment-to-population ratio was 42 percent in 2017.[4] Afghanistan ranks 168th in the human development index out of 189 countries in the 2017 HDI report.

In 2016, the newly formed National Unity Government presented its strategy in Afghanistan National Peace and Development Framework (ANPDF) to stimulate the economy and improve development outcomes. The ANPDF sets out national priorities that cover productive capacity, agriculture, trade, human and social development, and regional connectivity at thematic level aligns with those of IPoA. More than three years later, the ANPDF remains not fully operationalized. The government is still in the process of finalizing the National Priorities Plans (NPPs) needed to guide the implementation. If the IPoA is to be mainstreamed into the ANPDF, an assessment as to how the government’s national priorities correspond or integrate IPoA objectives has yet to be conducted. Moreover, the government requires well-defined development objectives that are backed up by robust metrics for measuring performance.

Off-budget aid interventions lack transparency in terms of goals and objectives. They remain fragmented in approach and implementation. Tracking off-budget aid assistance to the country remains challenging. The data is mostly unavailable to establish and improve linkages between the programs to both IPoA objectives or the government’s 5-years strategy.

The government has repeatedly called for channelling more financial resources through the national budget and aligning off-budget assistance with the government’s defined national priorities. The public financial management system’s fiduciary risks remain substantial and deter donors’ trust from funnelling additional aid through on-budget.

Despite the much-commended tax administration reforms that improved public revenue collection by 90 percent from 2014 – 2019, the unpredictable (and declining) international aid remains a vital element to finance around half of the national budget. The government needs drastic transformation in a decade to achieve IPoA’s objectives that demand sustainable fiscal resources.

The government has increased its focus to achieve fiscal self-reliance and to reduce aid dependence. Despite the macroeconomic vulnerabilities and weak economy, the government is showing a growing appetite to opt for loans as an alternative to reduced aid financing. Under the existing macroeconomic imbalances, there are valid concerns that given reduced aid levels and potential accumulation of external loans in the future could put Afghanistan on the trajectory of unsustainable debt.

Conclusion

A drastic transformation alone can make it possible to achieve the IPoA objectives; else the country needs to perform steadily well in the LDC category for decades to graduate. A sudden structural change, in many cases and forms, is not realistic. On a broader spectrum, IPoA has been optimistic on few fronts; it has not well incorporated the regional instability around the LDCs, institutional capacities, international assistance’s effectiveness and the political economy of the countries. The link between planning and implementation is missing, and improvements require revisiting the approach and engaging LDCs.

In the current context of Afghanistan, with high political uncertainty and increased violence, the country is way behind achieving the criteria of IPoA for graduation by 2020 and many years more. Fundamental structural and institutional changes are needed if Afghanistan is to provide the required service delivery, stimulate the economy, and scale up the private sector.

A coordinated multi-year approach and investment programs with clear and realistic targets of the international community and the government is required. Implementation of IPoA objectives calls for a clear plan on the follow up of IPoA that is owned and led by the country. With the current trend of events, another decade might barely suffice for the country to achieve the IPoA targets, given the need to strengthen the economic governance of the country further.

References:

[1] The conflict has inflicted heavy civilian casualties, loss of properties and caused destruction of critical infrastructure. We are illustrating the fiscal cost since the objectives of IPoA may be achieved if integrated within national budget of the government.

[2] Philip Barret. “The Fiscal Cost of Conflict: Evidence from Afghanistan 2005 – 2016”. April 2018. IMF Working Papers Series: 1.

[3] GDP per capita current in US Dollars. World Bank data accessed on December 27, 2019.

[4] ILO database accessed on October 27, 2019. https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/country-profiles/.